The Transparency in Coverage Final Rule, issued by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), requires health insurers to disclose pricing for covered services and items. Insurers must include the rates they have negotiated with participating providers for all covered services and items, as well as the allowed and billed amounts for out-of-network providers. Allowed amounts are the maximum rates insurers will pay for a given service and billed amounts are what providers have actually charged.

The new rule requires most health insurers to provide personalized information about consumers’ out-of-pocket costs for covered services via an online, self-service tool. An initial set of 500 “shoppable services” are supposed to be available to consumers in 2023, with the rest to follow in 2024.

Taken together, this information should provide consumers with a clearer sense than they can get today of what their health insurance plan will pay for, even if they see doctors who don’t participate in their health insurer’s provider network. With that information, people can theoretically make informed trade-offs about which healthcare providers to see.

Despite state, provider and insurer efforts to shine a light on prices and quality in healthcare, some corners of the industry remain dark. Drugmakers have come under fire for refusing to disclose how they set their prices. And pharmacy benefit managers—the middlemen who are hired by insurers and employers to negotiate prices and set formularies—have been sharply criticized for keeping the rebates they receive from drugmakers a secret. PBMs argue that their negotiations with the pharmaceutical must be concealed to hold prices down

Results from the previously implemented Hospital Price Transparency Final Rule may offer a cautionary tale on this front. The hospital transparency rules require hospitals to publish standard charges for all their services and items and to make the prices for the 300 most common services accessible in a consumer-friendly format. The rule took effect on January 1, 2021 but a year later, just 14% of hospitals were in compliance.

CMS set higher fines this time around, so insurers who don’t provide the required data will have to pay $100 per day per violation for each affected member, which could quickly add up for large plans.

For the most part, consumers remain in the dark about what they will be asked to pay after visiting a primary-care doctor or undergoing an inpatient procedure. In that way, healthcare is unlike every other aspect of the consumer experience in America. It would be unimaginable to leave a broken-down car with a mechanic before getting a cost estimate, for example.

The information should also allow Americans to project their out-of-pocket costs more accurately because the amount the insurer will reimburse should no longer be a mystery. Knowing the out-of-pocket costs before you incur them is a level of visibility Americans have been sorely lacking.

True healthcare price transparency would require purchasers to have direct access to all relevant information on prices and quality in a reliable and understandable format. This would give them the ability to choose the best alternative and put pressure on providers to lower prices and improve quality. Absent such competitive pressure, less efficient providers or those earning excess profits remain in the market, and prices will be higher than they otherwise would be.

Informed consumer choice requires adequate information on both cost and quality. If consumers are poorly informed about quality, they cannot make a fully informed purchasing decision and prices are unlikely to converge to efficient levels. In the absence of accessible and comprehensive quality information, consumers may inaccurately equate lower prices with lower quality, defeating the purpose of price transparency

The new insurance transparency rules follow the January 2022 implementation of the No Surprises Act, which protects consumers from unexpected charges for certain services. The No Surprises Act requires private health insurers to cover certain out-of-network bills at the same rates they would if the services had been provided within the health plan’s network.

In theory, this level of transparency could force healthcare prices down (though some economists warn it could also encourage some providers to raise their rates if they feel they’ve been underpaid). When the rates health insurers negotiate with healthcare providers are on full display, the companies paying for employer-sponsored health benefits may find reason to question insurers’ negotiating effectiveness.

Who Would Benefit From Price Transparency?

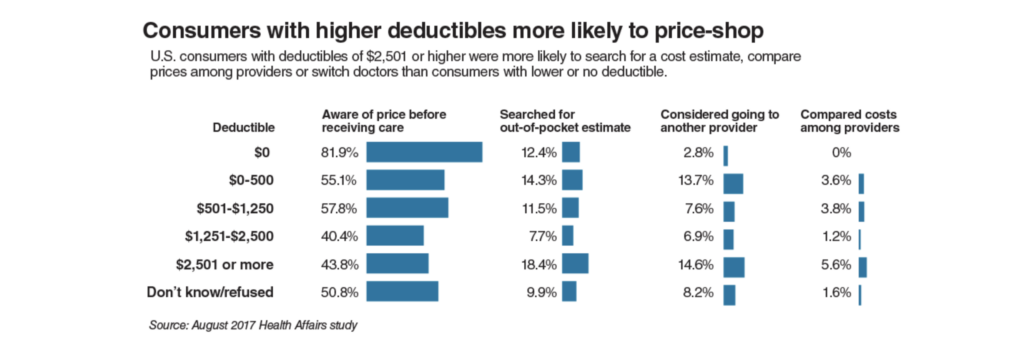

To date, most price transparency initiatives have targeted consumers, with the avowed goal of creating better-informed buyers who would use price and quality information to purchase lower-priced, higher quality care. There are structural reasons, however why consumers might not make effective use of transparent cost information.

Individual consumers are primarily concerned about the amount of out-of-pocket payment for which they will be responsible. For insured consumers, the price they pay for care is only a small fraction of the overall cost, with insurance picking up the rest. Two different consumers with different deductibles and co-payments could face significantly different out-of-pocket costs for the same identically priced service, depending upon the plan. Moreover, by the time a patient reaches a hospital, the out-of-pocket limit for many insurance policies may have been reached making the patient insensitive to price.

A second reason price transparency might not motivate consumers to become more discernable shoppers is that patients do not typically choose which hospital they enter. Rather, patients choose a physician and the physician’s admitting privileges determine where the patient goes. Available evidence suggest that most physicians admit the bulk of their patients to one hospital. If a patient wishes to go to another hospital, he must select a physician with privileges there. Over time, physicians likely would become more sensitive to differences in costs among various hospitals on behalf of their patients, but in the interim, the patient would have only partial influence over the selection.

The most receptive target of healthcare price transparency would be the nation’s employers, who provide insurance coverage for approximately 160 million employees and their dependents. Knowledge of insurer-negotiated prices would enable self-insured employers to demand lower prices and develop networks of high value providers. It would also enable employers to develop reference pricing for shoppable services, i.e., those that can be scheduled in advance by a healthcare consumer.

Recent Comments